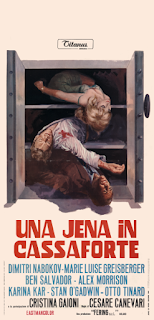

A Hyena in the Safe (1968)

This all-too little-known Italian cult film is a dizzying and dazzling gem. The curiously-titled A Hyena in the Safe (a literal translation of the film’s original Italian title, Una jena in cassaforte) is bursting with Pop art eye candy and bristles as a camp masterpiece that outclasses such bloated fare of the period as Candy (1968) and Myra Breckinridge (1970).

After stealing a cache of diamonds from Amsterdam eleven months earlier, a group of thieves gathers at an Italian villa – during Carnival, for some reason – to each retrieve their share of the loot. The diamonds are stored in a safe (submerged under water for some reason) that can only be opened by each of the thieves’ keys – which were presumably exchanged for their cut of the jewels…for some reason.

When one of the thieves fails to produce his key, discord, mistrust and murder ensue. At that point, about thirty minutes in, the film’s plot kicks into high (camp) gear. So does the body count.

Imagine a post-plot Modesty Blaise (1966) (or Topkapi [ 1964]) thriller that combines the comic-book touches of Mario Bava’s fumetti Danger: Diabloik (1968) with the murderous impulses of Bava’s later Agatha Christie-inspired giallo Five Dolls for an August Moon (1969). That pretty much sums up the plot of Hyena - but tells nothing of the style and presentation of this wacky, yet hypnotic adventure.

Slick and sometimes just plain silly, Hyena even beats the baroque animal-themed Italian film titles spurred by the popularity of Dario Argento’s The Bird with the Crystal Plumage (1970).

Characters

Each member of the cast is pitch perfect in performance – and their flamboyant cartoonish villainy. We start with “Klaus from Hamburg,” played by Stan O’Gadwin as a menacing Aryan-type that crosses the patented intimidations of Curt Jürgens with Patrick Magee. Then there is “Carina, from Tangiers,” played by Karina Kar, in for Omar, who we are told is “in hiding.” Carina plays, however ineffectually, to the European witchy and bewitching types seen in the Italian films of Barbara Steele.

Afterward, we meet “Steve from London” (Dmitri Nabakov – none other than “Lolita” author Vladimir Nabakov’s son, an erstwhile opera singer, racecar driver and, later, overseer of his father’s legacy) and not “Thomas, Dutch,” who lost his share of the booty in an unseen poker game (cleverly suggesting Ian Fleming’s “Casino Royale”) to Juan, from Spain (Ben Salvador) – playing to a pervy stereotype of the swarthy predator.

We also meet the dandy playboy drug-addict “Albert from Marseille” – the handsome Tom Brady-lookalike Sandro Pizzachero, billed here as Alex Morrison – with his supposed “fiancée” Jeanine (Cristina Gaioni), a dead ringer for Monica Vitti in Modesty Blaise. There are many reasons to believe these two are not, as they say, engaged to be married – but it all just goes to show that no one here is to be trusted or believed.

Nothing, however, prepares you for the brilliant Maria Luisa Geisberger as Anna. From the moment she steps (ever so provocatively) into the picture, literally in a hall of mirrors (recall the relevant The Lady from Shanghai [1947]), she possesses the film. As Boris’ “widow” – or whoever she is – this femme fatale commands the attention of the cast and viewers alike – from the beginning until the bitter end.

Remarkably, Ms. Geisberger and much of the rest of the cast were not regular film actors. A Hyena in the Safe is among these actors’ only credits. (Pizzachero would go on to do a few other Italian cult-classics including So Sweet, So Dead [1972] and The Teenage Prostitution Racket [1975]). If that suggests hacks or sub-par acting, it shouldn’t. All deliver great – if perfectly over-the-top – performances.

Direction

Perhaps the expert performances are a credit to director Cesari Canevari, known elsewhere for directing the first Emmanuelle film (1969) and later sleaze-fests such as The Gestapo’s Last Orgy (1977) and Killing of the Flesh (1982). Canevari’s direction here is superb. His actors deliver scintillating performances. And even when things slow down (Albert’s drawn-out withdrawal and, later, the garage drowning, for instance), there is an element of style that always comes to the fore.

Canevari co-wrote the dialog-heavy script with Alberto Penna, an obscure writer whose one of two other credits is on a later Canevari film, Il romanzo di un givane povero (1974), also among director Luigi Cozzi’s earliest writing credits. Despite all the patented lies and verbal histrionics, very little of interest is said – although getting rid of three of the main protagonists before the movie even starts is a very clever conceit.

What makes Hyena worth seeing, however, is what is on the screen: the outrageous fashions, the outlandish make-up (the diamond faces prefigure one of the baddies in the James Bond film Die Another Day [2002]) and the stunning villa, replete with observatory, pool dome and temple fountain. Not to mention the attractive actors – who take up a good deal of screen time.

Photography

All of this is captured by the little-known cinematographer Claudio Catozzo, whose few films were mostly directed by Cesari Canevari. Here, the camera is so busy, it almost serves as another character in the film. Catozzo’s restless eye darts between people and objects like a cat studying the room. Sharp jump cuts and reverse zooms (the opposite of what Bava and Fulci were doing at the time) give the editing a sort of staccato tempo. And the aerial shots give a superb sense of the vultures circling.

Naturally, there is a comic-book sensibility here. But we don’t get the odd camera angles or punchy calibrations of “Batman” or the exquisite compositions and brilliant miniatures of Bava. Here, Catozzo delivers a deliriously dynamic filmic version of a static page brought to life.

Among the film’s best shots are surely Anna’s entrance, literally in a hall of mirrors; the camera as it tracks a moving drinks cart (about 21 minutes in); the jeweler Callaghan’s spirit-of-death entrance; a Get Smart-styled sequence of Anna going through doors and passage ways (about 45 minutes in); the blue-light bar chat between Klaus and Juan; and Anna’s remarkably lengthy Mata Hari routine (52 minutes in), where the camera eroticizes her every move…without eroticizing her.

Perhaps the most dazzling scene of all is the penultimate scene, where madness becomes a dizzying kaleidoscopic fever dream of diamonds and demons. All of this makes Hyena worth the effort: even muted, this film transfixes.

Music

Hyena’s score and earworm main theme come courtesy of Gian Piero Reverberi, who is best known for “Last Men Standing” (a.k.a. “Nel cimitero di Tucson”) from the soundtrack to Django, Build a Coffin (also 1968), which was sampled by Gnarls Barkley for their hit “Crazy” – also featured in more than a few films and TV shows.

The main theme, what they call a “shake,” seems at odds with the film’s murder plot, though not too far away from Piero Umiliani’s equally earwormy “Five Dolls for an August Moon” theme. It is, however, playfully perfect for the film’s campy comic-book tone (consider, too, John Dankworth’s “Modesty Blaise” or Umiliani’s Baba Yaga theme).

Reverberi provides several nice “tension” cues, one even suggesting the “Get Smart” theme. And there’s a clever, though maddening, scene where a gong – and, later, a manic piano – “break the fourth wall” by going from the apparently non-diegetic (music the viewer hears) to the diegetic (music the film’s cast hears)…for some reason. It’s campy, even cliché, but effective.

Just like the rest of the movie.

Video

A Hyena in the Safe is a camp classic that seems not to have made much of an impact outside of Italy, if it had any impact at all in its country of origin. There seems to be no English-language dub version of the film and certainly no official video or disc release…anywhere.

I first saw Hyena on YouTube (since taken down), and it garnered my immediate attention and affection. I ended up picking up a grainy version of the film that looks like a TV grab. On my copy, the film’s trailer looks many times better and sharper than the actual film itself.

I hope that my fondness for A Hyena in the Safe, along with others who have written favorably of the film, will help sway one of the major players in Italian genre cinema (Arrow? Vinegar Syndrome? Synapse? 88 Films? Kino Lorber?) to consider tracking down an original copy of the film – if it’s even possible for such a thing to exist more than a half a century later – and offer us a good-looking version of this obscure yet desirable, umm, gem.

Thank you for bringing this film to my attention. And, Arrow Video, please bring this title to your faithful customers!

ReplyDelete