Who Killed Mary Whats’ername? (1971)

”Retired boxing champion tries to solve the murder of an obscure New York streetwalker.” - TV movie listing, Los Angeles Times, May 19, 1974.

So begins the seemingly unlikely premise of the offbeat, atmospheric and oddly endearing time-capsule, Who Killed Mary Whats’ername, or what a cheeky headline aptly dubbed “Apathy of a Murder.”

The 1971 film – which elsewhere lists the last half of the title as “What’s ‘Er Name” or “What’s Her Name” – stars Red Buttons as Mickey Isadore, the aforementioned boxing champion, and features Sylvia Miles as Christine, the hooker with the heart of gold, who was friends with the Mary no one cares about.

Mary is loaded with a terrific cast of then-unknowns who would go on to capture name recognition, particularly on television and most in comedies: Conrad Bain (Diff’rent Strokes), Alice Playten (Doug), Sam Waterston (Law & Order), Ron Carey (Barney Miller and Mel Brooks films), Earl Hindman (Home Improvement) and David Doyle (Charlie’s Angels). Great New York character actors like Antonia Rey, Dick Williams and Gilbert Lewis feature in small roles as well.

To its credit, the film is set almost entirely on location in New York City’s Little Italy on the lower East Side at a time when grungy was the nicest thing that could be said about it. Dangerous was probably more apt. These are New York’s real mean streets: the film has none, absolutely none, of the polish or artistry of the higher-minded Klute (1971) or Taxi Driver (1976).

Director Ernie Pintoff’s film has the amateur-auteur quality of early Brian De Palma and Paul Morrissey (Mary producer George Manasse worked on De Palma’s 1968 film Greetings as well). Like those De Palma and Morrissey films, Mary feels more authentic: grittier, darker, pulpier and, well, somewhat less contrived than its obviously manufactured plot. Pintoff uses a lot of hand-held camera and naturalistic lighting, giving the film a stark documentary look.

Moreover, Mary is startlingly – perhaps even perversely – free of the cynicism (and a lot of the violence) that marked so much of the New Hollywood films rocking cinema at the time. The popularity of films like Bonnie and Clyde (1967), The Graduate (1967), Easy Rider (1969) and Midnight Cowboy (1969 – rated X at the time) – even Klute, The French Connection and The Last Picture Show (all 1971) announced a new era of filmmaking that makes Mary’s decency and humanity seem quaint.

Mary tells us hope, optimism and compassion are not only possible, but necessary if we are meant to survive. The death of New Hollywood several years later tells us that no one cares either way. Once the blockbuster was born (especially by 1977’s Star Wars), cinema would come to mean escapism and comic-book fantasy.

The performances here are all top-notch and surprisingly natural – something that was not always so with De Palma and Morrissey in those days – and indicate that Pintoff is good with actors (something evident in much of his later TV work). One senses that the director allowed some level of improvisation among the actors as their characters and the interplay are remarkably believable.

Red Buttons (1919-2006), in particular, is a stand out as Mickey, the unlikely millionaire with a heart of gold. His Mickey is in every respect a fighter: he’s a former boxing champion who battles a diabetic condition (something fairly novel in 1971 cinema) while single-handedly seeking justice for poor dead Mary.

While Buttons was better known as a comedian, he proved here as well as in Harlow (1965) and They Don’t Shoot Horses, Do They? (1969) that he could hold his own in dramatic roles (Horses is why Cannon wanted Buttons for the role of Mickey).

It turns out that Buttons had a reason to make the film work: he apparently had a (unknown) “percentage deal” with the film’s production company, the Cannon Group, ensuring he got a take of the film’s success…which, sadly, probably did not amount to much – if anything at all.

Mickey’s daughter Della is played with equal parts warmth and zeal by Alice Playten (1947-2011), who herself was diabetic in real life. Only 23 when Mary was made, Playten had already built a substantial résumé as a theater actress. At the time, though, she was best known for, of all things, an Alka-Seltzer commercial.

Here, Playten shares a remarkable chemistry with Buttons: their scenes together are warm, realistic and convincing. Playten’s adult daughter feels plausible and right with Buttons’ busy-body father; indeed, their scenes together are among the most enjoyable in the film.

When someone asks Mickey why he’s investigating Mary’s death, he claims that he - a poor kid from a bad neighborhood – could’ve been her: “That’s why I’m doing it…partly.” While Mickey never explains what else motivates him, it’s pretty clear it’s because Mary was someone’s daughter (someone’s mother too). And Mickey’s daughter clearly means everything to him.

While it’s not really enough to motivate the plot of an entire film, Mickey’s fatherly instinct toward Mary is an extension of his love for Della and, however idealistically, an effort to help make the world a “better place,” safe for her, other daughters and girls, whatever their profession.

As the good-natured Christine, Sylvia Miles (1924-2019) plays, well, Sylvia Miles – the way no one else can or could: tough and bawdy, yet emotional and needy. Miles’s Christine is bookended by her almost opposite yet still-the-same appearances as Cass in John Schlesinger’s Midnight Cowboy (1969) and Sally in Morrissey’s Heat (1972).

While Variety dismissed Miles “in another of her bleached, tired hooker bits,” her Christine is really very touching and sympathetic. Like Mrs. Florian in Farewell, My Lovely (1975), Miles and Christine know their best years are a spec in the rear-view mirror. But they are survivors (until they’re not) and play the hand that’s dealt them with all they’ve got.

Perhaps the film’s most enigmatic or problematic figure is handsome Sam Waterston’s budding documentarian, Alex. His character is saddled with one too many red herrings, none of which are adequately resolved, making everything Alex does seem utterly incoherent. But his passivity – he claims “I am an eye” as a way to avoid involving himself in life – marks him at best as suspect (particularly to Mickey) and at worst complicit (all the herrings).

On the other hand, Alex’s combined lack of self-awareness – curiously, he reads Joseph Gelmis’s 1970 book “The Film Director as Superstar,” indicating he might dream well above his talents and ability – and feeling for others (his film is more important than the people in them) aptly symbolizes the selfishness, apathy and utter indifference – or ambivalence – referenced throughout the film and made explicit in its title.

Mary offers bit parts to Conrad Bain, David Doyle (as a repulsive john who at, one point, orders a drink, curiously saying “I’ll have another - less blood, more Mary”), Ron Carey (who was also in Pintoff’s previous Dynamite Chicken) and in a blink-and-you’ll-miss-him cameo, the Raging Bull himself, boxer Jake LaMotta, who here reprises his Hustler role as a bartender (about 22 minutes in).

Mary may take more than one viewing to properly appreciate or enjoy. It is missing some of the more stylish window dressing of most thrillers. Chandler’s baroque plotting, Christie’s clever puzzles, Nick and Nora’s sparkling dialogue and Walter and Phyllis’ devilish doublespeak are all more or less M.I.A. in Mary

Even the Italian giallo thrillers of the period – such as Dario Argento’s 1970 film The Bird with the Crystal Plumage - slather more decadence, luridness and bloody set pieces on their byzantine plots – likely in an effort to hide the contrivance at the heart of all such pulp-y tales.

By comparison, Mary is positively – and probably intentionally – ordinary. This film boldly eschews style (or some Hollywood definition of it) in favor of a documentary sort of realism; a way to seriously examine the existential problem at the heart of the film.

Consider that if the film’s title – its single-most lurid aspect – is, as Sight & Sound suggests, a “stray allusion to a world without humanity,” then the film’s purpose is to chronicle the odyssey of a “self-appointed crusader” whose own humanity seeks to redress the lack of humanity served upon one of society’s least fortunate.

Cannily, this makes Mickey the ultimate Chandler ideal: “Down these mean streets a man must go who is not himself mean, who is neither tarnished nor afraid. The detective in this story must be such a man. (…) He must be, to use a rather weathered phrase, a man of honor, by instinct, by inevitability, without thought of it, and certainly without saying it. He must be the best man in his world and a good enough man for any world.”

That Mickey goes into a world he knows little about – all real places in New York City’s Little Italy neighborhood, circa 1971 – but navigates steadily, indeed as well as if not better than Philip Marlowe himself, gives Mary it’s seductive ambiance.

Our amateur detective has such an endearing personality, he is able recruit a small band of deputy amateurs to help (including his loving, eager daughter) and offers Mary a level of humanity too often missing in most whodunits. In the end, Mary is a social drama (maybe even a family drama), wrapped in a mystery inside a documentary enigma.

Also appealing is Mickey’s motivation to solve the crime: not because it’s his job (which would make it a procedural) and not because of a professional or financial reward is at stake but because Mary deserves her own humanity. Buttons’ performance, in particular, really brings this home and it his interactions with others that consistently keeps the film engaging.

While Mickey claims early on that he’s learned “things that are extraordinary,” the only real “clue” he unearths – with Della’s help - is the film-within-the-film, Alex’s documentary. This “film” – not so much a finished product as various reels shot on Mary’s last night – winds up becoming a key to Mickey’s investigation.

Mickey, much like David Hemmings’ Thomas in Michelangelo Antonioni’s 1966 film Blow-up, avidly searches reels (!) of film looking for missing puzzle pieces. In the end, all Alex’s film delivers is one suspect (Boulting) and Mickey’s realization, after multiple viewings, that he (and everyone else) has mistaken Mary at a pivotal point for her daughter Angela. Solving…nothing.

That Alex’s film is of little or no avail to Mickey – and ultimately to Mary itself – seems to me to be the point. Not even the camera cares who killed Mary. If Alex is, as he says, “an eye” (which is also to say he is “an I”), then we see only what he sees, or maybe more importantly, what he wants to see.

On one hand, this suggests that documentary film – out of necessity – is as much of a crafted or plotted story as a feature film, say Mary. On the other, even unedited raw footage may not tell the whole or even a true story, something that resonates in an era when just about everyone carries a phone with a high-resolution camera – not to mention the ubiquity of police with body cams.

This meta-commentary seems to be director Ernie Pintoff’s contribution to the film. I think it lends a particular significance to Mary that isn’t often recognized. Pintoff himself was a veteran of documentaries. Watching Alex’s footage, it’s hard to imagine a real documentarian shot stuff this meaningless (like Christine mugging for the camera) and, well, just this bad…unless it was intentional.

(Recall, for example, Boulting protesting – as any john might – that he’d been photographed while meeting up with a hooker, yet in Alex’s footage of Boulting the hand-held, slightly out-of-focus camera couldn’t have been more than several feet away from Revolting Boulting – while an obvious lamp is lighting him and his potential date for the evening. This is also the shot where everyone mistook Mary.)

If Alex's film tells us anything, it's that Alex is not all that he seems to be. Mickey eventually seems to figure this out.

My introduction to Mary came three decades ago while I was researching the film’s composer, Gary McFarland (1933-71). By 1971, McFarland was a veteran jazz composer, arranger and vibraphonist with important records in his discography featuring the Modern Jazz Quartet’s John Lewis, Stan Getz, Bill Evans, Antonio Carlos Jobim, Clark Terry, Steve Kuhn and others.

McFarland’s first film score was for J. Lee Thompson’s 1967 mess of a movie, Eye of the Devil, starring David Niven, Deborah Kerr, Blow-up’s David Hemmings and, in an early screen role, the ill-fated Sharon Tate. The film – which was recently issued on Blu-Ray – is worth seeing for the cast. But it’s worth hearing for McFarland’s magnificent, fully-orchestral score (Film Score Monthly issued the soundtrack in 2008).

Sadly, there was no soundtrack issued for McFarland’s score to Mary - and little known about whether the original tapes even still exist. By my count, McFarland’s Mary score contains an astounding 40 cues totaling some 49 minutes, an exceptional amount of music for a low-budget 90-minute film.

There are, of course, several variations of the main theme and obviously repeated themes (particularly in the film’s third act), but they are brief. And some of the themes – surprisingly – last for several minutes.

The music, likely recorded around August or September 1971, is performed by a small group of musicians, most prominent among whom is McFarland himself on vibes – and possibly the various keyboards heard throughout (if they’re not manned by someone else like Warren Bernhardt).

Of the other unknown musicians, flugelhornist Marvin Stamm is the only recognizable voice heard, but then-frequent McFarland associate Chet Amsterdam is most likely here on bass. The guitarist(s) is anybody’s guess.

McFarland’s melancholy main theme is a real beauty, with a flute/vibes main line (haunted by a harpsichord accent that recalls the instrument’s hint of menace in Krzysztof Komeda’s “Rosemary’s Baby” main titles theme) offset by Stamm’s wistful horn.

Underscored by three keyboards, gentle bass, drums and percussion, the “Mary” theme is a sort of post-bossa nova that suits the film’s emotional pitch perfectly. It’s almost the opposite of what one might expect for this sort of movie, a sad ballad that suits Mary’s person rather than her profession.

Notable among McFarland’s other Mary themes (the titles are mine) include:

- “Downtown Cab” (1:28) at about the 00:06:25 mark: Mickey catches a cab downtown to this jazzy cue, another feature for Stamm. This cue might have been an outtake from McFarland’s 1968 album Scorpio and Other Signs; it’s similar to that album’s “Runaway Heart.” A later version of this cue is heard with McFarland’s vibes and whistle taking the lead.

- “Diner Funk” (3:42) at about the 00:15:21 mark: If you can hear it over Antonia Rey’s screams, this fun little riff plays as Mickey fights Whitey at the diner. My guess is that McFarland is manning the Wurlitzer. Roy Budd would knock off a similar piece for his score to 1973’s The Stone Killer, “Down Downtown” (a.k.a. “Jazz Source”).

- ”Dominick’s Trombone” (2:10) at about the 00:21:37 mark: Mickey first meets Val at Dominick’s (sp?), where no less than Jake La Motta is tending bar. The trombonist here sounds very much to me like Kai Winding (1922-83), who is not known to have previously worked with McFarland. The cue is repeated at Christine’s apartment at the 00:37:03 mark.

- “To Angela’s” (0:47) at about the 00:52:20 mark: Most of this jazzy cue, led by McFarland’s vibes, is heard while Mickey is in or around his rented convertible, heading to meet Mary’s daughter, Angela. It’s difficult to tell whether this is its own cue or part of another, but it’s not heard again in the movie. (Note: Right after this cue is heard, Mickey is seen running to the top of a mostly vacant warehouse where the Twin Towers, then under construction, are briefly viewed.)

-“The Hags Harass the Hooker” (2:14) at about the 00:59:56 mark: This eerie ostinato, spookily scored to harpsichord, vibes and percussion is heard as Mickey comes upon the vacant space where Malthus and the hags are harassing one of the neighborhood’s hookers. The piece is heard again at the 01:05:46 mark.

On Tuesday, November 2, McFarland wrapped up recording sessions for an original cast album and went to the 55 Bar on Christopher Street in the West Village, where he somehow ingested a dose of methadone. He was taken to St. Vincent’s hospital, where he was pronounced dead on arrival. He was only 38 years old. Who Killed Mary Whats’ername opened ten days later.

Who Killed Mary Whats‘ername was released by the then-fledgling Cannon Group, co-founded in 1967 by Mary’s executive producer, Dennis Friedland. Cannon had early success with Joe Sarno’s sexploitation hit Olga (1968) and Swedish “nudie cuties” such as Inga (1968), before hitting mainstream success with John G. Avildsen’s Joe (1970), on which Mary producer George Manasse was associate producer.

At the time, Cannon had a reputation for cranking out films with bargain-basement budgets. Indeed, Joe was budgeted at a mere $106,000 (about three-quarters of a million dollars in today’s currency) – among their most lavish productions to date.

Mary’s budget was likely about the same as Joe’s. Unlike Joe, few of Cannon’s films found an audience or made much money. Mary was one of those films. Things got so bad that Cannon’s founders sold their interest in the company for $500,000 in 1979 to Israeli cousins Menahem Golan and Yorman Globus – who famously made the company’s name a genre in itself in the Eighties and Nineties’ video market.

Mary was based on an original script by native New Yorker John O’Toole (1931-2013). O’Toole would go on to write and produce documentaries for TV and radio and even won an Emmy in 1979 for his TV miniseries adaptation of James Fennimore Cooper’s Leatherstocking Tales (which would also feature Mary’s Earl Hindman). Curiously, O’Toole never scripted another thriller or, for that matter, another feature film.

Cannon brought in Ernie (later Ernest) Pintoff to direct. Pintoff (1931-2002) got his start directing such comedy shorts as the Oscar-nominated “The Violin” (1959), narrated by Carl Reiner, and the Oscar-winning “The Critic” (1963), written and narrated by Mel Brooks. Pintoff later went on to direct documentaries, before spending much of the 70s and 80s directing low-budget features and episodic television. After suffering a stroke in 1995, retired to teach. He also wrote several books on film, a novel and a memoir.

Pintoff – who, I think, makes a cameo appearance in Mary outside of Victors Pharmacy (about 78 minutes in) as Mickey tries to extract gum from an empty gumball machine – wasn’t terribly keen on O’Toole’s script (dated March 1971). The director asked a young Jeff Lieberman, a former student of his screenwriting class, to “punch it up.”

According to Lieberman’s marvelous memoir, “Day of the Living Me,” Cannon intended Mary to “be their second step toward legitimacy and a chance to show that Joe wasn’t just a one-off fluke.” Guess it was.

In order for Pintoff to place him on the payroll, Lieberman was tasked with becoming the film’s location scout (more on that later). At the same time, Lieberman – who later wrote and directed his own cult classics, Squirm (1976) and Blue Sunshine (1977) – worked on Mary’s script.

Lieberman likely buffed up Mickey’s comic Jewish asides and sarcasm (e.g., Mickey calling Alex “Fellini” and so on) while strengthening the script’s underlying social commentary and satirical elements – something that would have appealed to Pintoff’s sensibilities.

For all of Lieberman’s efforts – and there is every reason to believe that he is the key to much that’s good about the film – he could not claim any script credit. The film finally gave him a non-descript “Associate Producer” credit and a brief cameo, looking out a tenement window about 11 and half minutes in. A total “Gee, thanks” moment.

Pintoff conspires with cinematographer Greg Sandor to render Mary in a documentary style that’s closer to what some may have seen on TV at the time than, say, the artier pretensions of something like Costa-Gavras’ Z (1969). Little wonder, then, that Mary found favor on late-night TV in the Seventies and on grainy VHS in the Eighties.

The choice, while certainly cheaper, gives Mary an effective immediacy: a sense of guerilla filmmaking akin to Melvin Van Peebles’ Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song (also 1971). Likewise, there is no effort to slather lipstick on the city or provide touristy shots and postcard vistas.

Here, there is a considerable amount of hand-held camera – the most effective of which catches Buttons running through the piquant streets of Little Italy, particularly during the few night sequences – and “fly on the wall” camera work that make the film feel effectively as though we were following along after Mickey rather than a mechanical storyline.

Mary’s murder, which serves as the film’s pre-title sequence, is especially well conceived. Smartly diverting from O’Toole’s blandly scripted killing, Pintoff’s camera captures the room’s porcelain-doll miniatures (a nice touch) and their displacement while the murderous struggle is mostly only audible. Naturally, this allows the director to hide the killer’s identity (revealed later in a flashback).

But its intentional averting of the gaze from the ugly murder of a woman – not, coincidentally, by someone she professes to love – to these dolls, or decorative play things, is a startling way to start the film. One could wish Pintoff kept this sense of (artistic?) urgency in the film’s denouement, where Mickey’s diabetic haze becomes ours: it’s all a blur of sounds signifying, well, not much.

Sandor seemed like an especially good choice for Mary. He photographed a number of B-pictures and “nudie cuties” in the Sixties. He worked with directors Ted V. Mikels and Monte Hellman, including uncredited work on the cult classic Two-Lane Blacktop (also 1971). He brings that same sense of rebellion to nearly all of Mary’s scenes.

Sandor was also one of the photographers who worked on Peter Bogdanovich’s documentary Directed by John Ford (again, 1971) and would famously go on to photograph Brain De Palma’s Sisters the following year. Surprisingly, Sandor worked on several more films in the Seventies, but nothing near as prominent as anything noted here.

Perhaps the film’s greatest asset is its setting. Mary was filmed during March and April 1971 entirely on location in and around New York City’s Lower East Side, in the city’s Little Italy neighborhood. The setting lends the film a certain grubby authenticity and lovingly documents what it must have looked and felt like to live in this ethnic community in the early Seventies.

Native New Yorker O’Toole’s original script set Mary’s apartment on 29th Street, ostensibly in the city’s Garment District, the site of several important scenes in Alan Pakula’s better-known Klute, from the same year. Lieberman, who was sent to scout Hell’s Kitchen, wisely determined that Little Italy served as a better setting for the film and set Mary’s tenement apartment at 186 Mulberry Street (another “girl in room 2-A,” for giallo film followers). Other locations include:

The grungy dive was located at 129 Mulberry Street, on the corner of Hester Street in Little Italy, a few doors down and across the street from Mary’s apartment.

In February 1972, only months after the film was released, Larry’s Bar became Umberto’s Clam House. Named for the restaurant’s founder, Umberto Ianniello – whose son, the infamous Mafia leader Matthew “Matty the Horse” Ianniello, used it as a hangout – the Clam House was put on the map, as it were, as the site of the murder of notorious New York mobster “Crazy Joe” Gallo a mere two months later. The murder was later dramatized in Martin Scorsese’s 2019 film The Irishman.

Umberto’s closed in 1996 due to a lack of funds but has since reopened in a location just a few doors up. Today, 129 Mulberry Street is the site of the Italian restaurant Da Gennaro.

Elgin Theater: Located at 19th Street and Eighth Avenue in the city’s Chelsea neighborhood, the Elgin Theater is where Alex and Della go to see the W.C. Fields Film Festival – which was really running at the cinema during the first half of March 1971 (followed by a Buster Keaton festival).

The theater began screening films there in 1942 but by 1968 Ben Barenholtz assumed management and converted it into a repertory and art-film house. The Elgin became famed for being the first for showing “midnight movies” in the early Seventies like El Topo, which was still playing midnights at the theater during the filming of Mary.

By late 1978, the theater stopped showing films and was sold to new owners. It reopened as the deco-oriented Joyce Theater in 1982, where to this day it regularly features dance-company presentations.

Bella’s Luncheonette: Located about two blocks from Mary’s apartment on the corner of Prince and Elizabeth Streets, Bella’s is the real-life diner where Mickey first meets Christine…and Whitey. The luncheonette – with the iconic “Drink Coca-Cola” sign on its angled corner – was a downtown staple for many years, offering the quintessential New York City diner experience that was still thriving well in to the Eighties. There is also a scene in Basquiat (1996) set in the Little Italy eatery.

By the time Bella’s closed shortly thereafter, the neighborhood had started becoming gentrified (read: trendy and expensive) and rebranded as “Nolita” (or “NoLIta”), short for “North of Little Italy. Café Habana took over the space, opening in 1998, and remains a popular dining destination to this day (the Lenny Kravitz video for “Again” was shot there in 2000).

Kips Bay?: A contemporaneous review of Mary in Port Chester, New York’s The Daily Item suggests part of the film is set in “what looks like Kips Bay.” This neighborhood, located on the east side of the New York City borough of Manhattan, is possibly where Mickey’s townhouse is situated.

If the scene about 51 minutes in to the film outside Mickey’s townhouse is any indication, Kips Bay may be right. Mickey’s rented car – a 1971 Chevrolet Caprice or Impala – appears parked in front of what looks very much like Kips Bay Towers, the sprawling brutalist condominium complex designed by the legendary architect I.M. Pei.

Beth Israel Medical Center: This 800-bed teaching hospital, located at 16th Street and First Avenue on Manhattan’s Lower East Side, Beth Israel is where Mickey’s earliest scenes appear. Oddly, but typical for films, these were among the last scenes shot (in mid-April 1971).

In 2013 the facility was renamed Mount Sinai Beth Israel, when the hospital became part of the Mount Sinai Health System. (The building itself, particularly as seen from nearby Stuyvesant Square, reminds me of the New York apartment house Dario Argento foregrounds in the second of his “Three Mothers” trilogy, the superb Inferno [1980].)

There is also a scene (about one hour in) in front of Paolucci’s Restaurant, located at 149 Mulberry Street. Established in 1947, that Italian eatery closed in 2005 due to the higher rents being charged by then.

For a film that garnered near-zero attention, awareness or much of an audience, Mary made the “news” on several interesting pre-release occasions. The first, according to an article in the April 9, 1971, Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, Buttons lost his Mary costumes (what Della aptly qualifies as having come from “an Army Navy store”) when his on-location dressing room caught fire. Seems like it could have had something to do with the fire staged in Alex’s apartment.

Even more interestingly, Mary got some second-tier press notice due to a far more notorious, yet substantially more iconic, historic and beloved movie filming in New York at the same time: The Godfather, of course.

The April 20, 1971, edition of the New York Daily News reported on a large crowd that had gathered (and nearly disrupted filming) the day before along nearby Mott Street at a fruit and vegetable stand to witness “the shooting” of Marlon Brando’s Vito Corleone. The article mentions the nearby filming of Mary at the same time, a block or so away – apparently, and not surprisingly, undeterred.

The Godfather wasn’t released until four months after Mary - on March 23, 1972 – but, of course, it is not only one of the best-known films ever made, it’s now considered among the greatest films of all time. Pintoff would later cast The Godfather’s John Marley, who played film executive and lover of thoroughbred horses, Jack Woltz, as the lead in his next film, Blade (1973).

While Mary’s peculiar and enduring charms are many, the film is not without its obvious faults. Indeed, the few who have bothered to notice see nothing but faults. Pintoff, however, gathers a particularly good cast but doesn’t give them much to do. Only Buttons and Miles get much, if any, decent dialogue.

Even their characters are not so much cardboard cutouts as skin-deep surfaces: their goodness or kindness are all you get from them. Everyone you see here – with the possible exception of the inchoate Alex - is exactly what you get: each their own single shade of grey.

In its zeal for documentary authenticity, this “thriller” is too-curiously lacking in thrills…even by 1971 standards. Considering his comic background, Pintoff’s pacing seems lethargic at best. Still, while I always enjoy coming back to Mary, I reel at the absolute absence of anything transgressive.

The closest we get to that is imagining Mickey pursuing Mary’s murderer because his life turned on whether he chose boxing – or whoring: “Look, pal, I grew up in a neighborhood like this. If I hadn’t been lucky, I could’ve ended up alone in an apartment just like that and who would’ve cared?”

This possibly hinted-at possibility suggests that in his younger days, Mickey, like Joe Dallesandro in Morrissey’s Flesh, may have done a little hustling to make ends meet. Such a hint would have given Mickey at least a spiritual connection to Mary.

But, alas, our Mary has no sex, no deviance, no perverts, no maniacs, no fetishes (okay, there is an old guy into women’s boots, “click click”) – nothing at all outrageous. Imagine a Mary - which has nothing to say about politics or the war, or sex or feminism for that matter – that’s more like Joe. Nobody even swears in Mary. Surprisingly, no one at Cannon picked up on any of this.

The danger Mickey faces throughout also seems all-too fabricated – that is to say, a writer’s construction – than real. The bikers, led by Hindman’s terribly-named Whitey, are more menacing-looking props than credible threats. And the hags are less Rosemary’s Baby’s elderly fanatics than Monty Python’s “Hell’s Grannies.”

Mickey’s final indignity – his inability to score something sweet in broad daylight (was there a pandemic at the time?) – seems a bit far-fetched as well. But as Mickey’s hypoglycemia rapidly consumes his consciousness, it helps to end the film on not one but two ambiguous notes: will Mickey survive? Will the murderer get away with it?

What the mean streets of O’Toole and Pintoff’s Mary ignores, Paul Schrader and Martin Scorsese’s Taxi Driver gets, or at least hints at several years later. Taxi Driver even casts Joe himself, Peter Boyle.

Indeed, the widely celebrated Taxi Driver makes Mary look and feel like a quaint period piece, exposing none of the racism, misogyny (Boulting is as close as we get here), exploitation or corruption creeping around every corner of the city and teeming below the surface.

That doesn’t make Mary any less entertaining. Just less relevant…and, possibly to its benefit, less paranoid, misanthropic and hateful. Despite its numerous deficiencies, and bleak title, Mary’s greatest asset is its genuine hope for humanity: something in short supply today.

Mary opened on November 12, 1971, at about three dozen New York City-area theaters as well as theaters in New Jersey and upstate New York. If the film opened elsewhere – and I can’t determine if it did – it was likely released in major U.S. cities, but to little or no notice.

Whether the tagline featured on the film’s poster – “Somebody just murdered your friendly neighborhood hooker” – was a bit of daring-do or purposely designed to sabotage the film, it surely helped keep Mary out of the American suburbs and rural areas, far from the sensitivities of the early Seventies’ “silent majority.”

Reviews were few yet hardly riveting. Variety said Mary was “[b]lessed with a small but professional cast, but cursed with a screenplay riddled with logical loopholes” while the New York Times similarly brushed off the film as “the dullest kind of action movie-making and the least service to an attractive cast of generally superior competence.”

Bergen County, New Jersey’s The Record called it simply “a lousy movie” while Port Chester, New York’s The Daily Item, proposing an unnecessarily academic pan invoking Clifford Odets, not inaccurately dismissed the “picture which looks like a part of New York today and sounds like the New York of 40 years ago.”

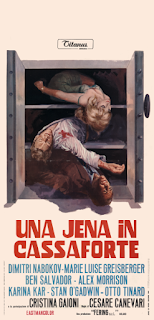

By June 1973, Mary was rebranded as Death of a Hooker and released to second-run theaters and the then-thriving drive-in circuit. Paired on at least one occasion with Sean S. Cunningham’s 1971 softcore “documentary” Together, Hooker at last brought Mary to small-town America, which by that time had its own father-daughter investigative team in CBS-TV’s Barnaby Jones.

The film’s revised poster didn’t do much better by the film than Mary’s original, proclaiming “This is PRO Country,” suggesting a weird sort of Americana that has nothing to do with the film. That the PRO here is PROstitution teases audiences to expect a certain softcore PORn that they weren’t going to get either.

The poster further pushes the porn and violence sub-text by hinting that “making love is easy…making it through the night is another story…!” Obviously, the advertisers were hyping a film no one was going to see (read that however you like).

John M. McInerney’s 1973 write-up of Death of a Hooker in the Scranton Tribune was among the film’s kinder and more thoughtful reviews: “This movie is appealing in a quiet sort of way but it doesn’t really reach out and grab an audience the way a first-rate mystery should.”

McInerney astutely and aptly notes that Hooker fails to “subordinate ‘whodunit’ plot mechanics to the clash of clever, compelling personalities in polished, witty dialogue, as Sleuth does.” Sleuth, Joseph L. Mankiewicz’s 1972 film of Anthony Shaffer’s play, starring Laurence Olivier and Michael Caine, provided much of the inspiration behind Rian Johnson’s superb 2019 thriller Knives Out and is all that McInerney says it is. Pity, Mary doesn’t strive to reach these lofty heights.

Mary popped up on late-night TV as early as 1974, likely appealing to programmers as a film that required little to no editing for content or language. Later in the decade, late-late-night TV showings of the film helped it become a minor cult favorite. The Thursday May 8, 1980, New York Times listed Mary, playing at 3 am on Channel 9 (WOR), with this everything and nothing description: “A lower East side murder revived” – showing just how socially conservative either the TV station or the Times was at the time.

First released on VHS by Video Gems in 1982 under its original title, then as Death of a Hooker in 1987, Mary was also issued on VHS in 1986 by Prism Entertainment with a striking but incongruous cover that posits it as a horror film (it is not).

There are also European issues of Mary on VHS – one on Pandora Video (that credits “Masterpiece Films, Coral Gables, Florida, U.S.A.”) with a copyright date of 1981 and another on Chock Video, which adorns the sleeve with stills from an altogether different film – suggesting that either no one claims ownership of the film or it’s been in the public domain almost from the beginning.

But, to date, the film has not been issued on DVD or Blu-Ray, with any sort of the appreciation or consideration it so richly deserves. Marginally watchable scans of the film (under both titles) are available on YouTube: Here or Here.

In 2022, I would love to see – and hear – a version of this film where, as Variety proclaimed, the “[c]olor camerawork by Greg Sandor is excellent; Angelo Ross has edited to a taut 90 minutes, and the score, by Gary McFarland is properly atmospheric.” But I’m not sure that’s even remotely possible at this point. I would see Who Killed Mary Whats’ername any way possible.

Afterword: While I’ve devoted a lot of words to this film, I think there is still more to say. Depending on the reaction – if any – to this post, I hope to explore more about this film’s value, significance and appeal.

Comments

Post a Comment