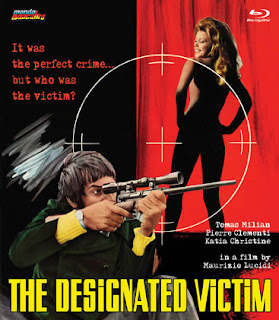

The Designated Victim (1971)

This all-too little-known giallo has finally secured a terrific Blu-ray release from the reliably good folks at Mondo Macabro. Long a favorite of mine (from an earlier German DVD release), this seemingly Strangers on a Train-derived melodrama is fascinating on many levels. Confusing? Maybe. Enigmatic? Yes. Fascinating? Absolutely.

Ad exec Stefano Augenti (Tomas Milian) wants to sell a portion of his wife’s shares of their company – mostly because he wants to run off to Venezuela, of all places, with his mistress, the model Fabienne (Katia Christine). But Stefano’s wife, Luisa (Marisa Bartoli), won’t let him. A chance meeting with a spectral stranger (Count Matteo Tiepolo) offers Stefano a surprising alternative: the Count offers to kill Stefano’s impeding wife if Stefano kills the Count’s domineering brother. Stefano isn’t initially convinced and plans his own sort of larceny. But then Luisa is found murdered…and suddenly things change.

If the set-up sounds familiar, the execution is anything but. The oblique plot and surprise finale hint at something fantastic (more on that later). Clearly, there’s more than meets the eye going on here.

One viewing reveals that The Designated Victim (also known as Slam Out and Der Todesengel [The Angel of Death]) is neither a typical giallo nor an average whodunit. It asks more questions than it answers. But they’re intriguing questions. For example, who exactly is “the designated victim”? Why is there only one; at least two people die? Perhaps “the designated victim” isn’t the one who dies.

Another question worth considering: what makes Stefano finally change his mind? In Hitchcock’s Strangers on a Train (1951) – which seems to inform this film’s exchange of murders – Guy never does Bruno’s murder. In Patricia Highsmith’s source novel (1950), Bruno blackmails Guy in to committing the murder. Neither scenario takes place here.

The Story

While The Designated Victim answers none of these questions, it presents a beguiling story that moves with an inscrutable logic that is positively dream-like. That significant parts of the film are set in the always oneiric Venice (think Don’t Look Now or even The Comfort of Strangers), suggests that there is, indeed, more here than meets the eye.

What I think The Designated Victim serves up – beautifully – is a particularly astute allegory about mass consumption. Consider ad-man Stefan and model Fabienne as, respectively, the symbolic architect and face (or body) of mass consumerism.

Likewise, consider the foppish Count, a hedonist burnt out and bored by “having it all,” and Stefano’s rich wife, Luisa (Marisa Bartoli), a lonely and depressed shut-in, as the human casualties of mass consumption. One wants to kill himself and the other has already committed social suicide.

So, who is “the designated victim”? As they say in advertising, “the target audience.” You. Us. All of us. Victims, all, of mass consumption. The Designated Victim is easily seen as the prequel – or the antecedent – of John Carpenter’s prescient and brilliantly-conceived They Live (1988).

Notice how the Shameless DVD cover shifts the target, or the gaze, incongruously, back to the woman? Mondo Macabro picks up this bait-and-switch iconography in their own release, seen above.The Shift

Unlike most giallo films, The Designated Victim has no murderous set pieces. Indeed, there are only two murders here and both happen completely off-screen. And the screen offers gorehounds only one measly spot of blood. In another shift away from the typical giallo, it’s not the black-gloved killer(s) whose identity remains unknown until the end; it’s the final victim. Fans of Argento, Martino or Fulci might be loath to consider The Designated Victim a giallo at all.

For many viewers, the horror here is likely to be found in the discernable, yet discomfiting shift of the film’s gaze. This feature alone gives the film a resonance few others have.

The Designated Victim subtly manages to avert the viewer’s gaze from the giallo’s usual trope of the objectified female (consider the opening titles sequence) to a somewhat androgynous and seemingly effete male (literally the rest of the film).

That the film manages this daring turn of the screw so subtly, yet so savagely, marks it as a brave, distinctive and – with a very appreciative nod to Kat Ellinger – transgressive tale with a deeper story to tell.

The SwapThe Faustian bargain that resolves Stefano’s “problem” is presented by one Count Matteo Tiepolo, elegantly played by the enigmatic French actor Pierre Clémenti (1942-99) as a foppish dandy right out of Oscar Wilde or, more specifically, “Dorian Gray.” One imagines an aging painting hidden somewhere in that lovely Venetian villa.

Clémenti is best remembered for pivotal scenes in Belle de Jour (1967) and as the chauffer Lino in The Conformist (1970). Strikingly attractive, yet daunting and daring in many ways, Clémenti also worked with Liliana Cavani (The Cannibals, also with Milian), Pier Paolo Pasolini (Pigsty - as a cannibal who utters only one word) and other audacious filmmakers such as Philippe Garrel on The Inner Scar (1972), in which he wears not a stitch of clothing.

Clémenti was arrested in 1972 on a likely hyped-up drug charge and wrote a book about the 18 months he spent in prison. He resumed his acting career in 1974 and worked steadily and often until his death in 1999. But nothing he did after prison seemed to match the verve and vitality of early work like this.

Here, Clémenti commands the camera and the viewer’s attention as the Count. Likely named for the 18th Century Italian painter Giovanni Battista Tiepolo, who painted in the Rococo style, Clémenti himself performs here in a Rococo style: he is ornate and excessive (reflecting the film’s take on consumerism), yet modishly anachronistic. Hardly surprising is the obvious chemistry Clémenti shares with the great Tomas Milian (1933-2017) as Stefano. Indeed, the two were said to be friends.

While Milian is best known for his Spaghetti Westerns and poliziottechi (and later appearances in American films and TV programs), he is surprisingly well-cast opposite Clémenti: something that speaks well to the open-mindedness and the expressiveness of both actors.

Here, Stefano is seen with his unnamed lady companion, whom he calls his "slave." Played by the actress Cathy Marchand, she is clearly modeled after the "Vivian Darkbloom" character in Vladimir Nabakov's Lolita, and portrayed by Marianne Stone in Stanley Kubrick's 1962 presentation of Lolita.The Dance

Milian and Clémenti have a chemistry that is positively palpable on screen. They bring an inner life to their characters that is remarkable, particularly given how shallow Stefano is. Stefano forges his way to a future – where he’ll have it all – that he’ll likely never know while the Count is clearly tired of dragging the weight of a past where he’s seen and done it all.

The Count also knows what’s really in store for Stefano – and like the good capitalist he is, the Count exploits Stefano’s weakness and greed for his own ends.

It is a pas de deux (and to be fair, the two do seem to dance with one another throughout) that is homoerotic, without ever being ostensibly homosexual. To watch this film without sound is to watch a beguiling dance piece; a ballet of need and want that is erotic but more transactional than sexual.

Both seem to affect the other, something this film brings out beautifully as well – whether that’s because each character is intrigued by the other or their problems or both. Milian, in particular, expresses how easily his focus – or the viewer’s gaze – can or could shift from Christine to Clémenti.

And Clémenti earns every bit of that shift. His best moment comes when Stefano pushes him in to the water at the lake house. And watch what he does when Stefano points a gun at him.

The Production

The Designated Victim is directed by Maurizio Lucidi (1932-2005), who also helmed such Italian oddities as Probability Zero (1969 – with Henry Silva and a story by Dario Argento), Stateline Motel (1973 – with Eli Wallach and Ursula Andress) and Street People (1976 – with then-James Bond Roger Moore and Stacey Keach).

Lucidi provides workman-like direction here. He waltzes along the border of the genre cinema of, say, Sergio Martino or Umberto Lenzi and the European art cinema of, say, Michelangelo Antoni or Nicholas Roeg. What he ends up with is neither as distinctive as any of those auteurs’ best films nor as bad as their worst, most excessive work. Oddly enough, Lucidi would finish out his career directing porn films.

What Lucidi excels at here is choreographing the entrancing dance between his two leads. To watch how the two men move about the screen reveals a director unafraid of collaborating with actors to bring a scene to life. The “action” belies what these two actors, particularly Milian, are known for elsewhere. But the tension and movement on display is compelling and surely the result of Lucidi’s assured direction.

The unusually intelligent screenplay is credited to Fulvio Gicca Palli, writer of Damiano Damini’s Confessions of a Police Captain (1971) and How to Kill a Judge (1975), both starring Franco Nero. Credit for the “story” goes to four others, including this film’s assistant director, Aldo Lado – himself a writer and director of intelligent films.

Fresh from assisting Bernardo Bertolucci on The Conformist (1970), Lado made his directorial debut six months after TDV with Short Night of the Glass Dolls in October 1971 and, like TDV, would set his next directorial effort, Who Saw Her Die (1972) in Venice.

The Designated Victim was shot by the great Aldo Tonti (1910-88), who photographed some of Italy’s best-known exports, such as Ossessione (1943, Luchino Visconti), Europa ‘51 (1952, Roberto Rossellini), Barabbas (1961, Richard Fleisher) and Casanova 70 (1965, Mario Monicelli).

Tonti also worked on two Charles Bronson films, Violent City (1970) and The Valachi Papers (1972) and photographed such genre fare as The Castle of the Living Dead (1964), with Christopher Lee, and A…for Assassin (1966), one of giallo writer Ernesto Gastaldi’s earliest scripts. He also helmed John Huston’s weird but spectacular-looking Reflections in a Golden Eye (1967).

For The Designated Victim, Tonti contrasts the slick industrial reality of Milan – all chrome, cement, mirrors and bright lighting – with the soft dreamlike classicism of Venice, all water and mysterious passageways (taking on a nearly Freudian significance). Tonti’s camera tends to capture Stefano in static two-shots with the women but elegantly tracks him with the Count, beautifully suggesting where he feels trapped and when he feels freed.

The Double

Mondo Macabro’s magnificent presentation of The Designated Victim includes a worthy commentary by Fragments of Fear podcast’s Rachael Nisbit and Peter Jilmstad. Their commentary, like much of their podcasts, delivers an informed, relevant and truly revealing discussion. While they are clearly often relying on prepared text, the sheer amount of information they offer up may require more than one listen to take in and appreciate.

While Hitchcock’s take on Patricia Highsmith’s Strangers on a Train may well inform TDV, Jilmstad and Nisbit indicate that there is more to this story than that mere write-off of a rip-off. And Nisbit brilliantly questions the reality of the Count in Stefano’s life – something that beautifully forces the viewer to consider the film in a whole new way (and reminiscent of another terrific recent Mondo Macabro release, the fantastic on multiple levels Queens of Evil [1970]).

Intriguingly, Nisbit questions the Count’s likelihood: in other words, what if Stefano imagines the Count…much in the way that Fight Club’s Edward Norton imagined “Tyler Durden”? It’s a fetching proposition. Even if the Count is real – as well as the demise that Stefano brings to him – what if, as Nisbit reasonably asks, none of the stuff that otherwise happens between the two is real? Perhaps all of this plays out entirely in Stefano’s mind.

What if the Count is Stefano’s idealized (or agonized?) version of himself? Or, alternately, what if Stefano’s Dr. Jekyll act (another way of smoothing over the consumerist angle) is a cover for the Count’s Mr. Hyde?

Maybe Stefano himself killed Luisa – believing he was the Count. The Count is so unusual (either as a modish hippie or an outdated relic) that he could be portrayed as an imaginary savior or villain or both. Someone who, or an idea which, possesses Stefano. Let’s face it, the Count seems like a “creation” to appeal to certain people (this viewer included). He appealed to Stefano – an ad man determined to come up with “what sells.”

What’s more, the Count’s inexplicable attraction to Stefano could be nothing more than Stefano’s own desire to get it all or die trying.

That takes The Designated Victim to possibly fantastic extremes. With a film so seemingly grounded in logic, this seems absurd. But is it? We watch Fabienne and the police chase Stefano – for whatever reason they suspect and just exactly where do they go? – we see he accomplishes his perceived mission. What do they get – and what do they know? Probably nothing.

So what happens next? We don’t know. What are we supposed to think? Stefano’s going down, of course; not necessarily for the death of the Count (if they can prove that) but for the death of Luisa (which they’ll find a way to prove). The film’s last shot seems to suggest he’s doomed either way.

Like the best film or book, The Designated Victim is all questions without any easy resolution. Mondo Macabro has posited this beautiful question mark of a movie in a glorious presentation well worth the consideration and appreciation of any giallo-phile or lover of Italian genre or art cinema. Highly recommended.

Comments

Post a Comment